How to Remember Chinese Characters

By Ash Henson

What the heck is this thing and what does it have to do with learning Chinese Characters? Read on to find out!

Wondering how to remember Chinese characters? This is your guide.

For more on how to learn Chinese characters more effectively, check out our free webinar. And if you're serious about learning Chinese characters, check out the Chinese Character Masterclass, a whole course on how to learn Chinese characters more effectively!

The Chinese writing system, made up of characters, or hanzi, is notoriously difficult to approach for most native English speakers. Difficult, of course, but not impossible.

If you didn’t grow up in a Mandarin Chinese or Cantonese speaking household, you’re probably looking at Chinese learning as a hobby (with a steep learning curve) or perhaps for work. You need a system.

The techniques I'm going to describe here deal with remembering character components by writing them, but the REAL point is the concrete steps you can take to remember characters and components.

Learning written Chinese is more than just typing pinyin or bopomofo into a device and getting the right character output.

Chinese learners sometimes ask, “who cares about writing? I just type characters with my phone or laptop!” Fair question.

However, if you learn how to write and then you forget, you can still recognize. If you learn how to recognize and then forget, you’ve got nothing!

Not convinced? If you really don't care about writing, then just learn your first 50 components using this method. Once you have about 50 stuck into your memory, your brain will be much more open to taking in character components directly and even then, you can still use these techniques without actually writing anything.

Employing hacks to Chinese learning, or at least your learning method, and understanding how characters really work as a system is key to remembering Chinese characters long term and with the least amount of effort possible.

Chinese language learning hack: don’t learn like native speakers

The traditional way, and the way a lot of native speakers do it, is to look at a model and copy it 50 times (check out our YouTube video about how non-native learners differ from native learners). This is called rote memorization.

I myself used this method when I first started out and I'm here to tell you, “Don't do that!” If you're going to learn Chinese, you have to be ready for the long road of hard work that lies ahead of you. That, however, doesn't mean that you have to maximize your suffering and minimize effectiveness.

Rote learning: “Don’t do that!”

If we are going to be learning thousands of characters, we need to minimize the amount of time learning each character while not lowering efficiency. Chinese people have a lot of time to learn their own language; you do not.

In fact, we want to increase our efficiency. Also, we want to minimize boring, repetitive tasks. The more enjoyable we can make our practice, the more likely we are to continue doing it. So, how do we do that?

First, I'm going to introduce a few hacks to reduce the burden of learning and to simultaneously make it more interesting. Then, I'll show some examples of how this works.

Hack #1: Reduce the amount of information you need to learn by using character building blocks

Realize that even though there are thousands of characters, you can break down the vast majority of them into smaller components (sometimes referred to as Chinese radicals or semantic components and sometimes even phonetic components).

The brute force method would be to learn the strokes and stroke order of individual characters. An easier and more efficient way is to learn the strokes and stroke orders of individual components. Then, when you learn a new character that is comprised of components you already know, you just have to remember the order that you write those components in.

Hack #2: Increase learning efficiency using organization, association, and visualization via memory objects for each component

No, this isn't some kind of New Age thing. In his book, Your Memory: How it Works and How to Improve it, Kenneth L. Higbee lays out the rules of effective memorization. I know “memorization” is a dirty word to some, but hey, if you're going to try and learn Chinese, you really need to roll up your sleeves and get ready to get your hands dirty!

As I was saying, rules #2, #3 and #4 are 2) Organization, 3) Association, and 4) Visualization. This means, the more you can organize the information you want to learn, the more you can associate it with things you already know or associate it with other things you want to remember, and the more you are able to form a mental picture of the thing you want to learn, the more effective your memory will be.

The technique:

For each component you want to learn, choose a memory object to represent the component. The best memory object is the real-world object that the component was created to represent, but also, you can do it in such a way that it maps to what the component looks like in modern Chinese. This works because it's easier for people to remember images (i.e., something they can visualize) than seemingly random lines.

Say you're going to learn 言 yán “speech.” This component originally depicted a tongue (originally written 舌) sticking out of a mouth (口) with an extra mark on the tongue denoting the movement of the tongue. You might want to visualize a mouth with a wagging tongue hanging out of it, like this:

Or, if you want to something that looks more like 言, picture a tongue with piano keys on it! Let's add some color too. The more vibrant your image is, the easier it will be to remember it.

That image is oriented the way we normally think about a mouth and a tongue, but in Chinese writing, sometimes things aren't oriented like we normally think of them. So, let's re-orient our image so that it's oriented like 言:

What's the point of all this?

The idea is that for each component, you want to have an easy to remember memory object. The piano keys on the tongue is there to remind you of what the component roughly looks like, in this case, the horizontal lines. So, before you even start to try and write your component, you'll have a rough idea of what it's supposed to look like.

How do I use my memory object?

Each time you want to write the component that the memory object represents, you think of the memory object and you write the component's strokes on top of the memory object. This gives you a mental grid to work with. It provides boundaries for your mind. And, you know that the component will fit your memory object, so your memory object will jog your memory of how to write the component. And remember: memory objects are MUCH easier to remember than the components themselves. Like this:

Note that the tongue and mouth memory objects have been de-emphasized in the picture in order to make the strokes stand out, but the idea should be clear: instead of just trying to conjure up strokes out of the ether, you write them on top of your memory object. Obviously, you don't actually draw the memory object. It's just in your mind!

Take it to the next level:

Using the real-world object that a component was created to represent will maximize the effect, rather than simply using something that looks similar to the modern form. For example, 言 is a depiction of a tongue sticking out of a mouth. If you were to choose, say, a guitar to represent it, it would be much harder to notice the meaning connections when 言 is giving the character's meaning.

If you're learning simplified Chinese, then you'll also have to learn 讠, which is the other form of 言. Of course, you can learn 讠using the same technique as 言 or, you could simply understand how 讠is an abbreviated form of 言 as the following diagram shows:

Image from the Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters

Will this help me remember Chinese characters?

Within the most common 2700 characters:

In simplified Chinese, 言 appears 5 times (plus it's a character in its own right) and its component form 讠appears 59 times.

In traditional, 言 appears 72 times (plus it's a character in its own right).

And there are quite a few components that are this common. If you make a memory object for each of them, you'll not only lower the boredom factor, you'll greatly increase learning efficiency by introducing organization, association and visualization to your learning!

Build a Chinese character memory object from scratch

Let's make a memory object for 工 gōng “work.” 工 originally depicted a shovel-like tool with a blade on one end, so let's use a shovel as our memory object:

Note that I choose a snow shovel since they are more square shaped and also choose a square handle, so that we can more easily use this image as a memory anchor for 工:

Since our memory object is based upon what 工 originally depicted, it will also help us to recall what it means when giving a meaning in other characters.

How to apply this to characters with more than one component

There are a few ways this can be done. I'm going to cover two of them here. Basically, 1) use a memory object for each functional component in a character, and 2) combine memory objects with actual character components (i.e., as it appears in the character, not as a memory object).

The idea here is that you want to balance the number of memory objects you create (and therefore have to maintain) with the amount of work it would be to learn a component straight up the old-fashioned way.

Use a memory object for each functional component in a character

If a component has a function in a character, then create a memory object for it. In other words, you want to avoid breaking up characters into components that don't have a function. For instance, you want to think of:

-

华 huá “glory; splendor; China” as:

化 huà + 十

and NOT as:

亻+ 匕 + 十.

If you break it up into three parts, you'll likely miss the sound connection between 华 huá and 化 huà. -

常 cháng “often; ordinary” as:

尚 shàng + 巾 “cloth” (常 originally meant “skirt”)

and NOT as:

⺌ + 冂 + 口 + 巾.

Once again, you'd probably miss the sound connection between 常 cháng and 尚 shàng.

Remember: good mnemonics will be based on the real structure of the character!

Sound and meaning connections are important for building up the ability to predict sound and meanings of individual characters you haven't learned yet. So, always be on the look out for them.

Task: remember a complex Chinese character using memory objects

到 dào “to arrive; to be at”

First, let's make memory objects for the functional components 至 and 刂:

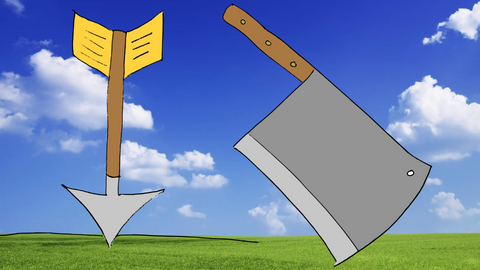

I'm going to choose this image, an arrow stuck in the ground, to represent 至 zhì “to arrive,” which originally depicted guess what? Yup! An arrow stuck into the ground (from which the meaning “to arrive” is derived). I drew my arrow in such a way that it would be easy to write 至 over it:

Notice how the top two horizontal strokes (一) of 至 match up at certain points on the feathers of the fletching. You can tweak your images in order to make it easier to recall your components. Also note that I drew 至 taller and skinnier than usual. Once you have the correct strokes memorized, you'll want to make sure to draw each component in its standard form. If you need help with stroke order, then draw the component while looking at a stroke order diagram a few times.

Now, let's make a memory object for 刂 dāo “knife,” which is the component form of 刀:

A big butcher knife ought to make it easy to remember that you're supposed to write a knife component. Now, let's write the 刀 on our memory object:

It should be obvious that trying to remember the shape of 刀 will be much easier when you're already thinking of a butcher knife. Now, I feel compelled to tell you that our butcher knife isn't quite representative of what the ancient form of 刀 actually represented, but that shouldn't matter here.

Making the story match the character

We have our two components now, so we can use them to make mnemonics. So let's make a memory story for the character 到.

Wait! We've run into a little problem. That is, 刂 is not the same as 刀. To say it more accurately, 刂 is a variant form of 刀. There are at least two ways of dealing with this:

-

learn to map both 刀 and 刂 to the same memory object

-

create another memory object for 刂.

The advantage to method 2 is that 刂 will have a more tailored memory object. In other words, upon seeing our memory object in our mind's eye, it'll be easier to remember 刂. The cost of method 2 is that we have to create another memory object. The advantage of method 1 is that we need fewer memory objects, while the cost is that we have to remember that our memory object could be one of two component forms.

For me personally, I prefer method 1, so here is what my memory story for 到 dào “to arrive; to be at” would look like:

You could just have this as a still image in your mind, but a movie is even better. Keep in mind, we're trying to remember the character for the spoken word dào “to arrive; to be at,” so in order to help minimize your memory burden, it would be best to learn that spoken word a day or two before you learn the character form (being sure to review the word in the interim).

Remembering a Chinese character with your full memory story

You see a green field with a blue sky. You hear a whistling sound as an arrow strikes the ground right in front of you. “It arrived!” you say out loud. Next, a cleaver comes flying through the air and hits the ground making the sound dào! Or maybe, the cleaver is alive, and says, “dào” out loud over and over again.

You practice your memory story each time the character 到 is up for review (perhaps in your Anki deck!). In my flash cards, I would prompt myself with dào “to arrive; to be at” and the correct answer would be my memory story (which would be written as the answer to my flash card). Then, practice writing the real character while thinking of the image above. When practicing, keep in mind that getting the memory story is more important than getting the actual character correct. Of course, on an exam, the actual character is more important!

Why does this work?

I'm glad you asked. There are many things going on here memory-wise:

-

visual objects are easier to remember than abstract symbols

-

meaningful objects are easier to remember than meaningless ones

-

stories are easier to remember than individual pieces of information

-

it's easier to remember a string of information if you can recall the first part of the string.

When designed properly, our memory objects act as hints for how to write a component by giving a rough outline. It's like if you forget someone's name. If you cycle through the alphabet in your mind, it's easier to recall their name because hearing the letter that the name starts with often triggers your memory of that name.

A visual object is easier to remember than a pile of strokes, both because it is something we can easily visualize, but also because the object itself is meaningful. So, we trade the difficult thing to remember (the meaningless pile of strokes) for something easy to remember (an object that we can visualize and has meaning). We tie the whole thing up in a story, because stories are easier to remember than a set of facts.

Applying memory objects to learning characters with more than one component. Again.

Method 2) Combine memory objects with actual character components (i.e., as it appears in the character, not as a memory object)

The idea here is to directly memorize a component that may only appear in one or two characters in order to save on the number of memory objects you need to remember. Say for example that you want to learn 制 zhì “to control, govern.” The left side of 制 only appears in 制. While 制 appears as a component in other characters, the left of 制 does not, so it's a good candidate for this method. Combining the actual component and our memory object for 刂 looks like this:

It's important to note, that it's better to save this method for after you've learned at least 50 components to give your brain time to get used to characters. Otherwise, it'll treat it as meaningless strokes and reject it like a transplanted kidney.

One thing you need to be careful of is that components aren't always what they look like. Sound confusing? No worries! I'll explain it in the next lesson along with how to keep track of all your memory objects!

In this part, I'm going to cover two topics:

1) Character components aren't always what they seem to be (I hinted at this earlier).

2) How do I keep track of all my memory objects?

Part 1: Components are not always honest

What? Components aren't honest? What does that even mean? Like I said earlier, understanding a character means understanding its functional components. So, sometimes, a component that you see in a character may actually only be a sub-component, or in other words, a component of a component. For example:

- In 就, 口 is not a component, but rather, a sub-component of 京. 就 is composed of 京 + 尤, and as such, it will not help you understand this character to break it down any further than that. What this means in a practical sense, is that 口 kǒu “mouth” plays no role in expressing the sound or meaning of 就 jiù “just; simply.”

- Or take 高 gāo “tall.” It is impossible to understand 高 by breaking it up into 亠+口+冂+口. In fact, none of these components give a sound or meaning in 高. Rather, these components work together to depict a tall building.

- Another example is 朋 péng “friend.” Even though it appears to be composed to two 月 “moon” (or “meat”) components, it's not. It was originally a depiction of a person carrying two strands of jade discs and came to mean “friend” via the notion of “a pair of strands.” So, if I try to understand 朋 by way of 月, I will fail.

There are other reasons that components may not tell us the truth, but I think you get the idea from the examples above. I hear the gears turning. You're probably asking yourself:

Why does this matter?

Understanding how a character breaks down into components is crucial for being able to see real sound and meaning connections between characters. Seeing real sound and meaning connections between characters is crucial for developing the ability make intelligent guesses about the possible sound and meaning of a character you haven't even learned yet. Of course, you may not be able to predict it exactly, but if you see the character in a meaningful context, you'll probably get pretty close.

Let's do an experiment. Look at the explanation for the characters below, then guess the pronunciation and meaning of the last one. One quick side note: The meanings I give below are the original meanings (not necessarily the modern meaning) because that is the only meaning directly tied to the character's form.

1st attempt:

Story: Wooden molds are made of wood, packed with grass, and used under the big, bright sun.

Story: We made a membrane from grass and meat under the big, bright sun.

2nd attempt:

Let's try this again, but with the correct character structure taken into account.

- 模 represents a word whose meaning is related to 木 “wood” and sounds similar to 莫 mò:

mó “wooden mold for producing tools” - 膜 represents a word whose meaning is related to 月 “meat” and sounds similar to 莫 mò:

mó “membrane”

Now, guess the sound and meaning of 幕. Write your guess down.

Answer:

Even if you can't guess the exact sound and meaning of 幕, you can probably at least come up with:

- 幕 represents a word whose meaning is related to 巾 “cloth” and sounds similar to 莫 mò:

mù “tent”

Well, we didn't get the sound exactly the same, but we did get pretty close. Knowing that the character sounds similar to mò cuts down the possible sounds significantly. And “tents” are definitely related to “cloth”. And, if you learn the word mù “tent” a day or two before you learn the character, the whole process is even easier.

Can you now make an intelligent guess about the sound and meaning of 摸? Think of how much easier new characters are to learn if you can already make intelligent guesses about their range of sounds and meanings. This is why understanding correct character structure and the role it plays is so crucial to efficient learning—and to making good mnemonics!

Does this kind of thing work all the time? Of course not! But, it does work a LOT of the time, making it very, very useful.

This also highlights the need for a source of reliable data for each character's structure! With reliable data, you can grow more quickly in your ability to make intelligent predictions about characters you haven't learned yet and to better recall the ones you have.

Part 2: How do I keep track of all my memory objects?

While the previous section covered some theory, this section is much more practically oriented and basically answers the question: If I'm going to learn characters using memory objects, how to I keep up with all of my memory objects? The short answer is to keep a notebook.

Then again, I'm old school. I like writing. If writing ain't your thing, keeping a spreadsheet works too.

Here is an example of what keeping a notebook might look like. In addition to actually drawing your memory object, write a description as well. The idea being if you look at it a year from now, that you can use the description and your drawing to recall your memory object. I left out the drawings for the memory objects for 言 and 讠because they looked a bit too phallic. Didn't want to make anyone blush! (I'm bald, so when I blush, the whole room knows it!). Of course, you want to keep all of the relevant information about your memory object, like its pronunciation (if it has one), the actual component, its description in words and a drawing of the memory object. You don't have to be a Picasso here. Actually, it's better NOT to be a Picasso, since he had trouble drawing things that look real! (we joke, we joke)

The main disadvantage of using a paper notebook is that you can't go back and alphabetize your list later. However, you could make an index in a spreadsheet (like pronunciation – component – page number). Or, you could have a notebook and give each letter of the alphabet a page. Write that letter prominently at the top of the page, and put the components that start with that letter on that page.

For those who aren't into putting pen to paper (weirdos!), you can do the same thing in spreadsheet format. The most challenging part of doing it this way is adding in images of your memory objects.

But, as you can see below, you can shrink your images while you're not looking at them, and then expand them as necessary.

The example above also shows another choice you'll need to make. That is, do you keep images of just your memory object by itself? Or, images of your memory objects with the characters/components they represent written on them? There is no hard and fast rule. You can do some of one, some of the other, and some of something else. What you really want to do, is put out the least amount of effort to get the maximum result. So, you might need to do some experimentation to see what works best for you.

Originally, my intention was to show how you can easily alphabetize your spreadsheet list according to pinyin, but for some reason, the memory object image files don't play nice. In fact, they don't play at all. They just sit there staring. I'm using Open Office Calc, but perhaps another spreadsheet program like Microsoft Excel or if you're a Mac user, Numbers, would do the trick. There is a workaround, though. Let me show you what that would look like:

Our workaround is to have a sheet for the memory object images, like shown above. Note that the cleaver is expanded, so that you can get a better view of it, but normally, you want to shrink it down to cell size. That way, it's easier to click on the surrounding cells if you need to.

On the original sheet, you don't put the actual image, just the image's row number in the new sheet (see below).

That is a little less convenient, but, since we only have to look up the images when we forget our memory object, we won't have to use it often anyway. Also, our word description may be enough in and of itself to help you remember your memory object.

Summary

The power of combining functional components and memory objects cannot be overstated. You want to get those functional components into your long term memory, while the memory objects are the perfect bridge for doing exactly that. The overhead associated with that, i.e., keeping up your spreadsheet, is minimal, but also, well worth your time investment. Using memory objects greatly reduces the amount of time and effort required and understanding characters in terms of their functional components brings a high degree of clarity, putting your brain at ease.

The advantage of the outlier method of learning what the characters ACTUALLY mean and how they evolved is it scales remarkably well. Using Outlier methods I can guess the sound AND meaning with around 80 and 90% accuracy respectively. Thank you! —Quizmaster Learn Chinese